By Mohamad El Kari

Visiting Lebanon today, it is difficult to escape the feeling that a collective sense of hopelessness has settled across the country, haunting and tormenting the everyday lives of the Lebanese people. Lebanon’s difficulties are manifold: deliberate economic depression orchestrated by the country’s ruling elite;[i] political paralysis caused by the Lebanese parliament failing to elect – for the 12th time – a president;[ii] and unhealed psychological scars following the Beirut Port blast in 2020 that ranks as the third largest urban explosion in history, after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings.[iii] But this veil of despair masks what was once a vibrant undertone of optimism and joy – four years ago, Lebanese people from all walks of life came together to reclaim their bodies, their streets, their city, and their country, in hope for revolutionary change.[iv]

‘You [political elites] bombed us, we [the Lebanese people] want to live to kill you in return’. Credit: Mohamad El Kari

Today, Lebanon marks the anniversary of the October 2019 uprising, alternatively called thawra (revolution) by idealists. On 17th October 2019, Lebanese people from all walks of life coalesced and rose up against a ‘kleptocratic ruling class of sectarian leaders and financiers that had captured and bankrupted the state after fifteen years of civil war (1975-90) and three decades of post-war neoliberal policies’.[v] Demonstrators objected to endemic corruption and demanded instant reforms to an absurdly clientelist and sectarian system ingrained at the heart of Lebanon’s political and economic system.

Four years on, however, the legacy and significance of the uprising remain a matter of controversy. For its critics, the thawra is synonymous with negative emotions and distressing memories, due in part to the internal divisions among protestors, increased state repression, co-optation strategies by the ruling elites, and the ongoing economic meltdown which all characterised the failure of the revolution.[vi] Advocates, on the other hand, argue that the thawra remains an ember of optimism in a gloomy mist of political hopelessness.[vii]

I spent two months in my Lebanese homeland earlier this year to carry out fieldwork for my PhD, which focuses on geographies of emotions within Lebanon’s October 17 protest movement, exploring how spaces, places, landscapes, and memories affect protestors politically and influence their feelings and emotions regarding the thawra and its aftermath. I was able to gather personal testimonies of Lebanese youth who recall complex emotions and painful memories encountered during the thawra. Here are some of their stories.

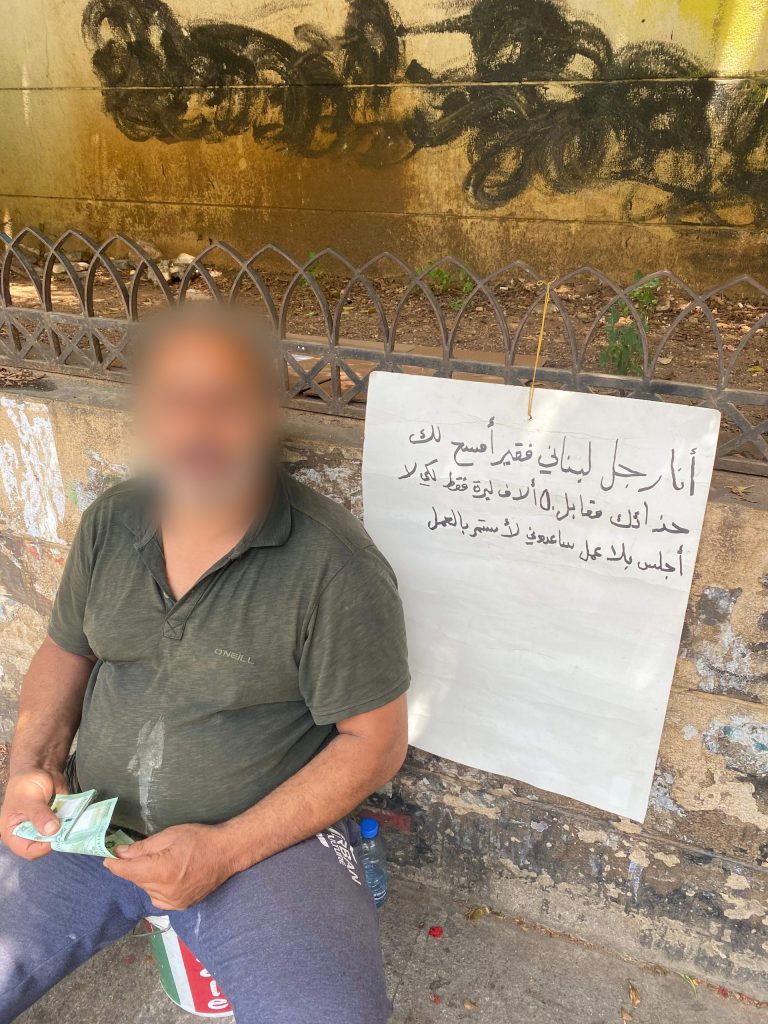

A man holding a poster that translates to ‘I am a poor Lebanese man willing to polish your shoes for 50,000 Lebanese Pounds (0.5 USD) so I do not become jobless. Help me keep working’. Credit: Mohamad El Kari

Political awakening and a new hope

Amongst the demonstrators in October 2019 was 20-year-old undergraduate student at the American University of Beirut (AUB), Fatima,[1] who is part of both the AUB secular club and organisation Mada, a political network and movement constituting of secular clubs in universities and syndicates across Lebanon.

For Fatima, the thawra was a revelation and a conviction that it was no longer a choice to be politically neutral, as she proudly reveals: ‘I was raised in a repressive and infantilising atmosphere where my family attempted to repress my political opinions and silence me, making me this numb machine that succumbs to their political ideologies. This made me feel isolated from what was going on in the world consider[ing] I was being sheltered from something I was going to be inevitably exposed to at university’.

When the protests broke out on 17th October, Fatima was finishing school, and she admits being conscious of certain aspects of her own political ignorance. She witnessed her friends embracing their own political activism, which motivated her to rebel with them. ‘I saw all kind of things happening, especially the teach-ins and heated debates that made me more politically aware. I witnessed violence, I saw people falling in love, I saw people rejoicing, dancing, and cursing politicians. For the first time I got this multi-faceted view of what Lebanon is’.

Four years later, Fatima still views the thawra as part of her daily life. ‘The way we do it for me and for those in Mada and the AUB secular club is that we run for elections, we hold daily discussions, we protest, we hang posters, we invite experts to give a talk, we go on television to speak’. It seems that there is no one dimension or direction to resisting amongst youth today, and there is hope this will bring change. For example, one year after the thawra, thanks to students like Fatima, there was unprecedented success for independent secular groups in student council elections, over those aligned with the traditional political parties.[viii]

The thawra encouraged many to see another side of Lebanon, and of themselves. ‘This is where my feminist political identity developed,’ Fatima professes. ‘I saw women being at the forefront of the revolution. I saw brave women standing up for themselves and fighting against the sectarian class, like the heroic women that kicked a police officer in the face. Seeing this as someone who was still in school was a steppingstone for my adulthood and shaped who I am. I felt that one day I can be one of those women. In fact, I am now’.

Hope graffiti covers Le Grey Hotel in Beirut, severely damaged as a result of the Beirut port explosion. Credit: Mohamad El Kari

Deep despair and hardship

The legacy of the thawra is one of political activism, but also one of distress. Anger and humiliation are common shared sentiments amongst youths I interviewed, as they revealed painful memories of this mass revolt that continue to affect them today. I spoke to 24-year-old graduate, Mona, who worked with think-tanks in the Middle East, researching youth participation in the thawra.

‘The thawra was the first time I participated in a protest movement and will be the last,’ she told me in a dispiriting tone. ‘I was very hopeful at first, I sensed a feeling of solidarity I never experienced before. I felt that people had my back, and we shared the same vision for this country. I started asking political questions when we used to have dinner with my family, which was a taboo back then. I questioned my aunt about the reasons she supports Hezbollah. I am not scared or intimidated to ask questions anymore. I felt the urge to learn and the right to know, unlike in the past where I believed it was too complicated to understand politics’.

Unfortunately, this optimism for change was soon overshadowed by utter hopelessness. Mona shares a painful memory of the march to mark the first anniversary of the Beirut Port explosion on 4th August 2021 which impelled her to distance herself from activism. As protestors expressed their outrage over the political elites’ ineptitude and corruption in the aftermath of the blast that killed 180 people, injured more than 6,000, and caused massive destruction across the city, the Lebanese military used lethal force against them.[ix]

‘I had some hope that the Lebanese authorities will be afraid of us as we were well equipped with tear gas to protect ourselves from the brutality of security forces. Like cockroaches they compelled us to leave. I remember this vividly as I was with one of my closest friends. We started crying, we literally failed, there was nothing we can do. Everyone was fleeing from the tear gas and water cannons. I kept crying for feeling hopeless. That night completely changed my perception towards Lebanon. I now separated myself completely from Lebanese politics as a result of [the] hopelessness I felt after that night,’ she cried.

Today, Mona lives in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and works as a senior communications executive. She is one of many who have joined the exodus of Lebanon’s most educated citizens, to search for jobs and education abroad in the aftermath of the thawra, because of the continuing social, economic, and political crisis.[x]

On the four-year anniversary of Lebanon’s thawra, the impact and significance of this historic event remains unresolved. This transformative moment is also one of the most disputed protest movements in contemporary Lebanese politics. It is crucial to revisit personal testimonies and critically reflect on these competing emotions and painful memories to understand the myriad ways Lebanese youth currently engage with and feel about the thawra, their perceptions of change, and how this influences the actions they will take in the future. The hope, despair, fear, and joy embodied in the diverse Lebanese narratives reflect diverging perspectives and timeframes, but also attitudes to Lebanon’s convoluted past and the quest for a better future.

[1] Interviewees names have been changed to ensure anonymity.

References

[i] World Bank (2022) Lebanon’s Crisis: Great Denial in the Deliberate Depression [Online] available from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/01/24/lebanon-s-crisis-great-denial-in-the-deliberate-depression

[ii] Al Jazeera (2023) Lebanon’s parliament fails to elect president for 12th time [Online] available from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/14/lebanons-parliament-fails-to-elect-president-for-12th-time

[iii] Al Hariri, M., Zgheib, H., Abi Chebl, K., Azar, M., Hitti, E., Bizri, M., Rizk, J., Kobeissy, F. and Mufarrij, A., 2022. Assessing the psychological impact of Beirut Port blast: A cross-sectional study. Medicine, 101(41).

[iv] Cornet, L. (2022) An Emotional Diary of the Lebanese Revolution [Online] available from https://phmuseum.com/news/an-emotional-diary-of-the-lebanese-revolution

[v] Makdisi, K., 2021. Lebanon’s October 2019 Uprising: From Solidarity to Division and Descent into the Known Unknown. South Atlantic Quarterly, 120(2), pp.436-445.

[vi] LCPS (2021) Why did the October 17 Revolution witness a regression in numbers? [Online] available from https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/articles/details/2462/why-did-the-october-17-revolution-witness-a-regression-in-numbers

[vii] LSE (2023) Lebanon Unsettled: The contentious geographies and histories of the October 2019 uprising [Online] available from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2023/07/31/lebanon-unsettled-the-contentious-geographies-and-histories-of-the-october-2019-uprising/

[viii] Arab Reform Initiative (2021) Lebanon’s student movement: A new political player? [Online] available from https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/lebanons-student-movement-a-new-political-player/

[ix] Human Rights Watch (2020) Lebanon: Lethal force used against protestors [Online] available from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/26/lebanon-lethal-force-used-against-protesters

[x] Financial Times (2023) More than half of young Arabs in Levant and north African pin hopes on emigrating [Online] available from https://www.ft.com/content/0ef960d8-1282-4fa9-a009-e24eebeab0e7

This publication was produced as part of the XCEPT programme, a programme funded by UK International Development from the UK government. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.