By Mohamad El Kari

Members of Soldiers of God. Credit: An-Nahar

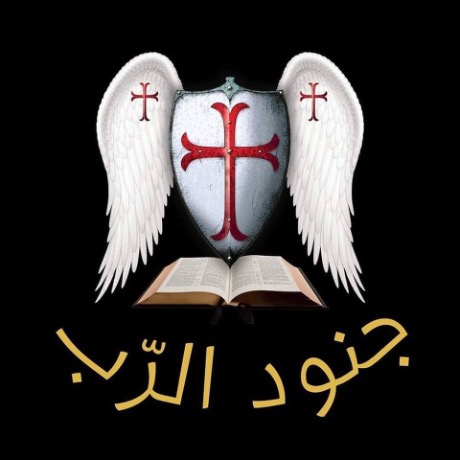

They are a group of Lebanese muscular tattooed men dressed in uniform black t-shirts, some of them heavily bearded, and carrying provocative religious iconography and symbols.[i] They are not Muslims, but Christians. They call themselves Jnoud al-Rab (Soldiers of God) and lead their own political, religious, and spiritual uprising, guided by the word of Jesus Christ as they interpret it.[ii] Their coat of arms is shown on their cars, mopeds, and t-shirts: a picture of the wings of Saint Michael the Archangel and a shield decorated with the cross of Jesus Christ, all sitting above the Holy Bible.[iii]

Soldiers of God claims that it carries out the teachings of Jesus Christ and is entrusted with his commandments. It defines itself as neither a party nor an organisation, but a militia group formed with the aim of protecting Christians and offering reassurances to residents worried about rising levels of crime – including armed robberies, carjackings, handbag snatches, and the theft of internet and telephone cables – in the majority Christian neighbourhood of Achrafieh in Beirut.[iv]

Self-security in Beirut is already a concern as Hezbollah conducts security patrols, checks the identities of passing citizens, interferes in the movements of the Lebanese security services, and blocks journalists from moving freely in the areas under its control.[v] The rise of far-right Soldiers of God has raised fears that Achrafieh will join this self-securitisation and paramilitary policing phenomenon, bringing Beirut back to the time of the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) when the state collapsed, militants controlled the streets, and the city was ideologically divided into the Christian East and Muslim West. These fears are increasing in light of the ongoing political paralysis and economic depression that has afflicted Lebanon since 2019, which crippled the state apparatus and is fuelling poverty in the worst shock since the civil war.[vi]

Soldiers of God’s coat of arms. Credit: Soldiers of God

Who are the ‘Soldiers of God’?

Soldiers of God was originally founded in late 2020 in a Christian residential neighbourhood in eastern Beirut by Joseph Mansour, who leads the group today. It soon spread into other Christian areas, notably Achrafieh.[vii] In Beirut, one legacy of the civil war is that the militarisation of urban space has been normalised.[viii] With the decline in the presence of official security services due to the ongoing crises in Lebanon, a variety of security mechanisms have been occupying the city and recreating sectarian territories, limiting residents’ everyday practices and use of public space.[ix]

One such mechanism was a ‘neighbourhood watch’ initiative, launched in Achrafieh in late 2022, which was the window through which Soldiers of God entered the heart of the neighbourhood. Headed by MP Nadim Gemayel – a member of the right-wing Christian Lebanese Kataeb Party – the initiative contracted a specialised security company to guard Achrafieh, provided that the guards were unarmed, and soon 120 young men were working as ‘guardian angels’ to offer reassurances to residents worried about crime.[x] Many of these guards went on to join Soldiers of God, which now consists of nearly 300 young men who are also referred to as ‘guardian angels.’ They patrol the streets of Achrafieh every night from 18:00 to 06:00, with a reported annual budget of £260,000.[xi]

Joseph Mansour, the group’s leader. Credit: Soldiers of God

The majority of these men are working-class, and reports indicate that the group’s nucleus was formed by former prisoners who worked to protect branches of Société Générale de Banque au Liban (SGBL) from Lebanese depositors, who were robbing banks and staging sit-ins to access their own savings in the aftermath of the October 2019 uprising, also known as the thawra.[xii] The majority of members also come from political and ideological backgrounds that support the Lebanese Kataeb Party and the Lebanese Forces – the party’s military arm – who have a complex history of deadly violence during the civil war.

Soldiers of God’s online presence often reflects on this violent part of Lebanon’s history, and its actions seem to be inspired by the military experience of the Lebanese Forces. In one post on its Facebook page, Soldiers of God paid tribute to a fighter from the Lebanese Forces who was killed in the Chekka massacre, which occurred in 1976 during the Lebanese civil war. During the massacre, Palestinian fighters and the Lebanese National Movement killed around 200 Christian people in the towns of Chekka and Hamat, in retaliation for the Tal al-Zaatar massacre, in which Lebanese Maronite militias, led by the Lebanese Forces, killed thousands of Palestinian refugees in Beirut. According to Soldiers of God, the fighter it was commemorating was a ‘martyr’, who died liberating the road that leads to the ‘holy’ land of Chekka.[xiii]

A clip showing members of Soldiers of God patrolling the streets of Beirut. Credit: Soldiers of God

Standing against the ‘outsiders’

When Soldiers of God patrols Achrafieh, it does so in purported defence of the Christian lands against the ‘Islamist peril’.[xiv] A video published by the group on its social media platforms shows members on their nightly patrol, presenting themselves as defenders of the Christian majority neighbourhood against ‘criminals’ and ‘outsiders’.[xv] This ‘othering’ rhetoric was also used during Lebanon’s civil war to refer to Palestinian refugees in Lebanon after they were expelled from their historic land in 1948, and more recently in post-war Lebanon to describe Syrian refugees.[xvi] Through its use of language, Soldiers of God contributes to a culture of fear and paranoia that encourages many Lebanese to turn to its sect for a sense of belonging, further reinforcing ‘the territorialisation of sectarian identities’.[xvii]

The ‘other’ refers not just to Syrian refugees, however, but to any non-Christians, particularly supporters of Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, two major Shiite Muslim parties in Beirut. Although Lebanon’s civil war officially ended in 1990, sectarian violence has continued to break out periodically in Beirut. In one notable incident in October 2021, deadly clashes between the Lebanese Forces and supporters of Amal and Hezbollah erupted – hailed at the time as one of the worst episodes of violence in Beirut since the end of the civil war – after the Shiite parties organised a protest calling for the removal of the judge who was responsible for investigating the Beirut port explosion.

According to an army intelligence investigation, Soldiers of God played a part in the shooting against Amal and Hezbollah supporters, which resulted in the death of seven and wounded dozens.[xviii] It is unclear who fired the first shots, and both sides were quick to blame the other. One account suggested that the fighting started when armed Hezbollah and Amal supporters entered the Christian neighbourhood Ain El Remmaneh, and supporters of the Lebanese Forces stood up to protect their neighbourhood. Whatever the origins of this particular clash, Soldiers of God had used it to further foment sectarian fears and prejudices. The army investigation revealed that members of the militia wrote religious slogans and drew crosses in a number of Christian neighbourhoods the night before the fighting started.[xix]

In another outbreak of violence, in December 2022, young men on motorcycles carrying flags of Morocco were beaten in the Achrafieh area by members of Soldiers of God. The young men were celebrating the historic victory of the Moroccan national football team and their qualification for the FIFA World Cup semi-finals in Qatar, but were mistaken for members of Hezbollah and Amal as they travelled from west Beirut, a Sunni-dominated neighbourhood.[xx]

In defence of Lebanon

According to Soldiers of God, it is not just the welfare of Christian neighbourhoods that’s at stake, but the welfare of Lebanon. The group proclaims itself to be the protector of God on earth, to defend its sanctities in response to the relative secularisation of Lebanese society. Yet, with the rise of Soldiers of God, personal freedoms, civil liberties, and individuals’ lives are endangered as the group employs violence against those who it claims are threatening Lebanese traditional values and customs.

In June 2022, the group vandalised a billboard in Achrafieh which had been decorated to celebrate Pride month. The same day, it posted a video accusing the LGBTQI+ community of promoting satanism and posing a threat to their children.[xxi] In August 2023, members of the group also attacked an LGBTQI+ friendly bar in Beirut by derailing a drag show and trapping people inside the bar while shouting their disgust.[xxii]

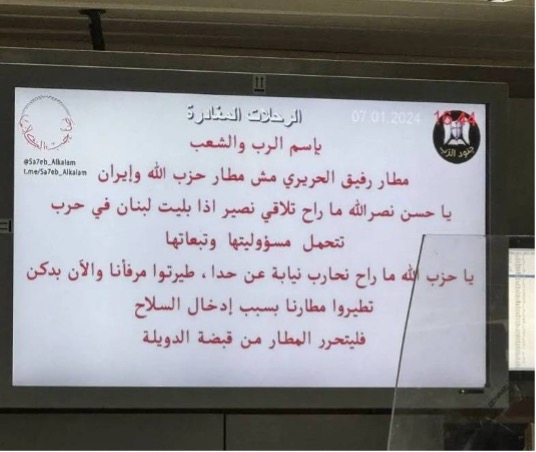

In January 2024, Soldiers of God took over flight screens at Beirut International Airport to assert its position as the defender of Lebanon, displaying a message for Hassan Nasrallah, the head of Hezbollah. The message said: ‘In the name of God and the people. Beirut airport doesn’t belong to Iran or Hezbollah. Hassan Nasrallah, you won’t find support if you curse Lebanon with a war you can’t handle. We will not fight on behalf of anyone. You took away our port now you will take away the airport because of your weapon transfer. Let the airport be free of you’.[xxiii]

According to Roula Talhouk, director of the Centre for Islamic-Christian Documentation and Research at Saint Joseph University in Beirut, this rhetoric ‘is a reminder of the Christian fighters during the Lebanese civil war, who used to put crosses on machine guns and tanks. They were clearly saying to the enemy “I am bombing you in the name of God”’.[xxiv]

The message displayed on the screens at Beirut airport. Credit: L’orient Today

Are we back to the time of religious militias?

Sectarian violence did not end with the civil war, but the rise of the Soldiers of God is reminiscent of darker times in Lebanon’s history, when militias enforced sectarian, territorial divisions. The decline in the presence and capacity of Lebanese authorities and their official agencies, due to state collapse occurring at multiple levels, is paving the way for sectarian conflict to return as armed groups take security matters into their own hands.[xxv]

There is also a real worry about sectarian violence as Soldiers of God is closely tied to, and financed by, former warlords and militias who participated in the Lebanese civil war. At the beginning of the civil war, Nabil Sehnaoui, a wealthy Lebanese man, used his familiar networks and resources to establish and finance the Lebanese Forces militia.[xxvi] Today, the bulk of the financing of Soldiers of God falls on the shoulders of the son of Nabil, Antoun Sehnaoui, who is the Chairman of the Board of Directors of SGBL.

Soldiers of God feeds into, and uses, existing divisions and tensions in Lebanese society to promote its cause. By playing on fears and suspicions of the ‘other’, the group exploits the legacy and memories of the civil war to enhance feelings of anxiety and strengthen identification with its movement. Some see Soldiers of God simply as a Christian answer to Hezbollah, reinforcing sectarian divisions and paramilitary presence at a time when Lebanon is facing economic and political paralysis.[xxvii] With an absent state, and Hezbollah pulling Lebanon into a war with Israel, the country’s future is unclear. In the meantime, its capital city continues to be a site of struggles over the meanings of national identity and the civil war’s legacy.

[i] L’orient Today (2022) Who are Achrafieh’s Soldiers of God? [Online] available from https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1304447/who-are-ashrafiehs-soldiers-of-god.html

[ii] Soldiers of God (2023) [Facebook] 25 July 2023. Available at https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=670093338494283&set=a.628163606020590

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Jnoud El Rab (2023) About Us [online] available at https://www.jnoudelrab.com/about-us/;

Reuters (2022) Beirut neighbourhood watch echoes troubled past [online] available at https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/beirut-neighbourhood-watch-echoes-troubled-past-2022-11-27/

[v] AlHurra (2022) The Eyes of Achrafieh… guardian angels or an introduction to self-security and division in Beirut? Translated by El Kari, Mohamad. [Online] available at https://bit.ly/3wysNVf

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] AlAkhbar (2022) Soldiers of God… the beginnings of self-security? Translated by El Kari, Mohamad. [Online] available at https://bit.ly/4bUMdnD

[viii] Graham, S. (2012) ‘When life itself us war: on the urbanisation of military and security doctrine’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (1) 136-155.

[ix] Fawaz, M., Harb, M., and Gharbieh, A. (2012) ‘Living Beirut’s security zones: an investigation of the modalities and practice of urban security’. City & Society 24 (2) 173-195. Wane, D., and C. Larkin. “Negotiating Lebanon’s urban boundaries and sectarian space: Syrian refugees in Beirut and Tripoli.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (2022): 1-20.

[x] AlAkhbar (2022) $330,000 annual salary budget: Guardian angels protect Achrafieh. Translated by El Kari, Mohamad. [Online] available from https://bit.ly/49Auxfx.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] AlMajala (2023) Everything you need to know about the Soldiers of God in Lebanon. Translated by El Kari, Mohamad. [Online] available at https://bit.ly/49Ez7JB

[xiii] Soldiers of God (2023) [Facebook] 5 July 2023. Available at https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=658014909702126&set=pb.100064808677829.-2207520000&type=3

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Soldiers of God (2022) [YouTube] 19 November 2022. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=18wK0NICufU&t=41s

[xvi] Kikano, F., Fauveaud, G., and Lizarralde, G. (2021) ‘Policies of exclusion: the case of Syrian refugees in Lebanon’. Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1) 422-452; Serhan, W. (2014) ‘Palestinians in Lebanon: A racialised minority or one of many other’? Arab Studies Quarterly 39 (3) 923-937.

[xvii] Larkin, C. (2010) ‘Beyond the war? The Lebanese post memory experience’. International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 42, 615-635; Seidman, S. (2012) ‘The politics of cosmopolitan Beirut’. Theory, Culture & Society 29 (2) 3-36.

[xviii] Hubbard, B., and Santora, M. (2021) Deadly clashes in Beirut escalate fears over Lebanon’s dysfunction. [Online] available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/14/world/middleeast/beirut-lebanon.html

[xix] El Houri, W. (2021) Deadly clashes in Beirut show Lebanon is a country of no accountability. [Online] available at https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/deadly-clashes-in-beirut-show-lebanon-is-a-country-of-no-accountability/

[xx] Houssari, N. (2022) Appeals for calm after Moroccan motorbike convoy in Beirut causes tension. [Online] available at https://www.arabnews.com/node/2215106/amp.

[xxi] Christou, W. (2023) Explainer: Who are the Soldiers of God targeting Beirut’s queer community? [Online] available at https://www.newarab.com/news/who-are-soldiers-god-targeting-beiruts-lgbt-scene

[xxii] Asharq Al Awsat (2023) Soldier of God group derails drag show in Lebanon. [Online] available at https://english.aawsat.com/arab-world/4506636-%E2%80%98soldiers-god%E2%80%99-group-derails-drag-show-lebanon

[xxiii] Middle East Monitor (2024) [Instagram] 7 January 2024. Available at https://www.instagram.com/reel/C10BSNYNJA4/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=5dd587f5-5dbd-44e0-8752-9e67952541aa

[xxiv] France 24 (2023) Lebanon paralysis grows as security chief bows out [Online] available at https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230303-lebanon-paralysis-grows-as-security-chief-bows-out; France 24 (2022) In Lebanon, Soldiers of God threaten the LGBT community and condemn civil marriage [Online] available at https://observers.france24.com/en/middle-east/20220715-in-lebanon-soldiers-of-god-threaten-the-lgbt-community-and-condemn-civil-marriage.

[xxv] AlArab (2022) The soldiers of God group in Lebanon raises concern. Translated by El Kari, Mohamad. [Online] available at https://bit.ly/49ROyxK

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] France 24 (2023) Lebanon paralysis grows as security chief bows out. [online] Available at https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230303-lebanon-paralysis-grows-as-security-chief-bows-out

This publication was produced as part of the XCEPT programme, a programme funded by UK International Development from the UK government. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.