By Clara May

Beirut is the posterchild for a divided city.[i] 15 years of fighting during Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990) saw the capital city split by ethnic, religious, and physical lines. These divisions did not end with the war. Over three decades later, sectarianism, segregation, economic inequality, and violence are a lasting part of Beirut’s post-war legacy.

The physical reconstruction of the city centre in post-war Beirut is believed to have played a role in these enduring divisions. When the reconstruction process began, many Beirutis saw it as an opportunity for society to heal. The public domain could be remade and revived, and in this way a space for reconciliation would be built.

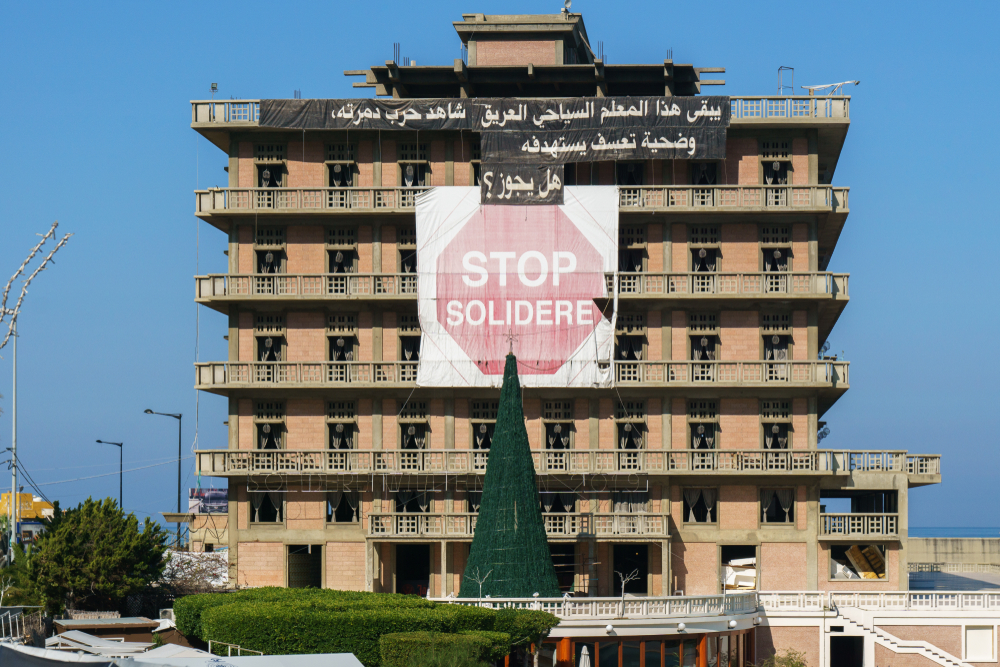

Solidere building site in Beirut. Credit: Shutterstock/David Dennis

Instead, the work, which was carried out by the private company Solidere, has been accused of promoting a culture of ‘amnesia’ around the civil war, as well as exacerbating socio-economic divisions. When Solidere rebuilt Downtown Beirut, they sought to remove all physical remnants of the war. In their place, a shiny new imagined centre was built.

But burying traces of war does not necessarily mean the past is buried too – and failing to create a unified space may be contributing to a divided society.

Nejmeh Square in Downtown Beirut. Credit: Shutterstock/Sun_Shine

‘We don’t need to look at the past’

Solidere’s reconstruction process, which began shortly after the war ended, seemed set on destroying all traces of recent history, and streets and buildings quickly fell prey to the bulldozers. By 1993, 80 per cent of structures in Downtown were damaged irreparably – yet only a third of this had been caused by the war itself.[ii]

For many, Solidere’s reconstruction of Downtown is the embodiment of the state’s policy of amnesia. The Taif Accord signed in 1989 to formally end the civil war proclaimed that there was ‘no victor and no vanquished’ in Lebanon. It suggested no mechanism for dealing with the legacy of fighting, nor did it mention victims. By circumventing the issue of responsibility, the state could begin to move forward. At the same time, it encouraged a culture of forgetting, leading to accusations of a state-sponsored amnesia in the country. One activist noted that ‘the downtown is the core of the reconstruction ideology — that we don’t need to look at the past’.[iii]

It’s been claimed that, for ‘communities of difference’ to be successful, there must be a ‘studied historical absentmindedness’.[iv] Given a general amnesty law in 1991, a broadcasting censorship law in 1994, and a law in 1995 enabling ‘the missing’ to be classified as ‘dead’, it seems unlikely that remembering the past would yield justice in the present. This ‘amnesia’ could therefore help to promote harmonious co-existence.[v] For some, forgetfulness is seen as ‘an antidote to future conflict’.[vi]

The Holiday Inn damaged by shelling during the civil war. Credit: Shutterstock/Catay

As Lebanese scholar Hermez remarked, however, it was hard to speak of the reconstruction ‘without referencing the war it was trying to render invisible’.[vii] Research has found that memories were not just tied to the buildings themselves, but in the ‘empty spaces’ that replaced them.[viii] By destroying ruins, but providing no memorial or monument to commemorate what had taken place, Solidere left a void.[ix] Publicising memories can help with the healing process, as it can allow for a better understanding of the past and an opportunity to respect other’s versions of the same events.[x] With no common memorial, civil society groups were left to mark the war unofficially on their own terms.

Protecting heritage

One study on post-war Beirut highlights the concept of negative heritage, which describes ‘cultural symbols and spaces that through trauma have become the repository of negative memory in the collective imagination’.[xi] Yet, while ruins may hold negative memories, they have the potential to be mobilised for positive purposes. One activist, speaking of the renowned Barakat building, claimed it had a role to play in encouraging understanding ‘because it is a beautiful building that has been destroyed … and you can see how something really important becomes used or abused for no reason. When you are there you are just forced to question the fact of why you go through a war’.[xii]

The erasure of negative heritage in Beirut also had positive outcomes by bringing people together in a ‘crusade’ to preserve heritage.[xiii] One initiative working to safeguard Beirut’s heritage, which was formed when the founder and his neighbours were facing eviction from their house, is made up of young people who were not part of the war generation.[xiv] In uniting people under a common cause, Solidere’s destruction of heritage may actually be paving the way for reconciliation. Notably, a recent study highlighted that involving youth in such initiatives may act as a barrier to future violence.[xv]

The Barakat building in 2019. Credit: Shutterstock/JossK

As well as erasing traces of the civil war, Solidere used the reconstruction process to promote another past. The focus on pre-civil war history, seen in the Heritage Trail which stretches from the Canaanite era to the late Ottoman period, suggests a desire to propagate a legacy of peaceful coexistence, ‘exemplified by the presence of Muslim and Christian places of worship next to Bronze Age, Iron Age and Hellenistic archaeological sites’, and reinforced by the building of public spaces around these sites.[xvi]

Daily life in Downtown

Promoting a selective version of the past is not enough to change the present, however. For many Beirutis, the new Downtown hinders opportunities for everyday coexistence. The rebuilding of Beirut’s centre was seen as ‘vital to peacebuilding’, as it provided an opportunity to ‘create a rare shared public sphere’ in a fragmented post-war society. Prior to the war, Downtown was remembered as a ‘vibrant, open space’ where people could mix freely. As one activist recalled, it was ‘a place where people needed to adjust to the fact that they are there with others who don’t have the same colloquial perspective … but they needed to interact with’.[xvii]

The reconstruction changed this. With the newly-built high-end apartments and boutiques well beyond the reach of the average Beiruti, Downtown was seen as an exclusive area which favoured the wealthy. As a result, the once bustling city centre transformed into ‘a culture-free ghost town for the rich.’[xviii]

The new open-air shopping centre, Beirut Souks. Credit: Shutterstock/Fotokon

But individuals can create new facts on the ground. In Downtown, multiple mass public protests, such as the Cedar Revolution in 2005, the ‘You Stink’ movement in 2015-2016, and the thawra uprising in 2019, saw the exclusivity of the site challenged, as people from across the political, social, and sectarian spectrum came together to protest.[xix] One survey examining how Lebanese youth understood their heritage found that many saw Martyr’s Square in the heart of Downtown not as ‘a historically significant square’, but as a symbol of revolution.[xx] The quelling of the thawra, however, alongside the Beirut Port explosion and the Covid-19 pandemic, ultimately saw the blockading of public spaces in Downtown, and the closure of shops, restaurants, and entertainment spaces – again denying Lebanese society a shared public place. Today, the city centre is once more the playground for ‘the princelings of the uber wealthy’.[xxi]

Protestors gather in Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square after the Beirut port blast. Credit: Shutterstock/Ali Chehade

Urban ruins may provoke painful memories or provide reminders about past experiences, but it is the way they are utilised that really matters. In Downtown, a violent past was wiped clean to begin the story of a peaceful future, but the experiences of people living in these spaces can help to create new narratives. Further research into the experiences of Beirut’s residents will increase our understanding of the role that ruins, and their reconstruction, can play in reconciliation. In the meantime, instances of violence and peace will continue to shape the city’s spaces and the lives of their inhabitants.

St Georges Hotel, Beirut. Credit: Shutterstock/Catay

[i] Fregonese, S. (2012). Urban Geopolitics 8 Years on. Hybrid Sovereignties, the Everyday, and Geographies of Peace. Geography Compass, 6(5), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00485.x

[ii] Makdisi, S. (1997). Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere. Critical Inquiry, 23(2), 661–705. https://doi.org/10.1086/448848

[iii] Nagle, J. (2017). Ghosts, Memory, and the Right to the Divided City: Resisting Amnesia in Beirut City Centre. Antipode, 49(1), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12263

[iv] Barber, B. R. (2003). Jihad vs. McWorld (Corgi ed.). Corgi Books.

[v] Khalaf, S. (2003). Civil and Uncivil Violence in Lebanon: A History of the Internationalization of Communal Conflict. Columbia University Press.

[vi] Larkin, C. (2010b). Beyond the war? The Lebanese post‐ memory experience. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 42(4), 615–635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002074381000084X

[vii] Hermez, S. (2017). War is coming: between past and future violence in Lebanon (First edition.). University of Pennsylvania Press.

[viii] Larkin, C. (2010b). Beyond the war? The Lebanese post‐ memory experience. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 42(4), 615–635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002074381000084X

[ix] Barak, O. (2007). “Don’t Mention the War?” The Politics of Remembrance and Forgetfulness in Postwar Lebanon. The Middle East Journal, 61(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.3751/61.1.13

[x] Gillis, J. R. (1994). Memory and Identity: The History of a Relationship. In J. R. Gillis (Ed.), Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity (pp. 3-24). Princeton University; Larkin, C. (2010a). Remaking Beirut: Contesting memory, space, and the urban imaginary of Lebanese youth. City & Community, 9(4), 414–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01346.x; McDowell, S., & Braniff, M. (2014). Commemoration as conflict: Space, memory and identity in peace processes. Palgrave.

[xi] Fricke, A. (2005). Forever Nearing the Finish Line: Heritage Policy and the Problem of Memory in Postwar Beirut. International Journal of Cultural Property, 12(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739105050150

[xii] Nagle, J. (2017). Ghosts, Memory, and the Right to the Divided City: Resisting Amnesia in Beirut City Centre. Antipode, 49(1), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12263

[xiii] Larkin, C. (2010a). Remaking Beirut: Contesting memory, space, and the urban imaginary of Lebanese youth. City & Community, 9(4), 414–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01346.x

[xiv] Puzon, K. (2019). Saving Beirut: Heritage and the City. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(9): 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1413672

[xv] Selim, Mohareb, N., & Elsamahy, E. (2022). Disseminating the living story: promoting youth awareness of Lebanon contested heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(8), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2022.2099445

[xvi] Nagel, C. (2002). Reconstructing space, re-creating memory: sectarian politics and urban development in post-war Beirut. Political Geography, 21(5), 717–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(02)00017-3; Puzon, K. (2019). Saving Beirut: Heritage and the City. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(9): 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1413672.

[xvii] Khalaf, S. (2006). Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj. Saqi; Nagle, J. (2017). Ghosts, Memory, and the Right to the Divided City: Resisting Amnesia in Beirut City Centre. Antipode, 49(1), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12263

[xviii] Alkazei, A., & Matsubara, K. (2021). Post-conflict reconstruction and the decline of urban vitality in Downtown Beirut. International Planning Studies, 26(3), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2020.1839388; Naylor, H. (2015, January 1). Beirut Rebuilt its Downtown after the Civil War. Now it’s got everything except people. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/beirut-rebuilt-its-downtown-after-the-civil-war-now-its-got-everything-except-people/2014/12/31/3b72e8b5-1951-409e-8b3d-1b16275d7f3d_story.html; Rahhal, N. (2019, December 5). Lebanon’s hospitality industry suffering from economic and tourist crisis. Al Arabiya. https://english.alarabiya.net/business/economy/2019/12/05/Lebanon-s-hospitality-industry-suffering-from-economic-crisis-and-lack-of-tourists.

[xix] El Kari, M. (2023). Four years on from Lebanon’s 17 October revolution. ICSR. https://icsr.info/2023/10/17/four-years-on-from-lebanons-17-october-revolution/

[xx] Selim, Mohareb, N., & Elsamahy, E. (2022). Disseminating the living story: promoting youth awareness of Lebanon contested heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(8), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2022.2099445

[xxi] Dettmer, J. (2023, October 25). As Lebanon’s border simmers, life in downtown Beirut goes on (for now). Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/lebanon-border-simmers-life-downtown-beirut-financial-crisis/

This publication was produced as part of the XCEPT programme, a programme funded by UK International Development from the UK government. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.